Originally published on 13 September 2017 by United for Quality Education www.unite4education.org

I often puzzle over how it is that though we know so much about the spectacular failures of privatisation initiatives in the social and education sectors, international agencies and governments, from the UK to the USA and Liberia, are hell-bent on pursuing more, and not less, of this decidedly dodgy product. And this is despite the accumulation of facts: that we, as a public, are worse rather than better off.

Look around, and public services from education, water, transport, health, prisons and other essential services, are being broken up at a rate of knots and outsourced to private business. This is accompanied by the shady promise: that private means ‘more efficiency’ and ‘more equity’.

Proponents of turning public services into market exchanges point out that markets are more efficient because competition generates ‘innovation’. Yet there is evidence that not only have new private sector monopolies been created ─hence, buying up competition generating innovation┬ but these giant conglomerates trade in everything from prisons to education and the repatriation of asylum seekers. There is little evidence of innovation here unless under-investment and asset stripping counts.

On the equity front, they also argue that ‘the market’ does not care about our social class, gender, or indeed the colour of our skin. As a result, the indifference of the market —as opposed to a bureau colonised by middle class interests—regarding these social facts makes it a far superior organiser of social goods and services.

Yet again, the evidence is compelling. That where market ideology has dominated the reorganisation of societies and their social and education sectors, as in the case of countries such as the UK, the United States of America, Australia, and indeed Sweden, the direction of travel is more rather than less social inequality.

A huge number of best sellers in 2014 – from Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century to World Bank economist Branco Milanovic’s The Haves and the Have Nots– all pointed this out. And yet, still, the pursuit of the marketising and outsourcing of everything has gone from strength to strength rather than the reverse.

Faced with such facts, is this a case of illusion, delusion or what? Surely we are not that stupid to be constantly complicit in being duped? Or, to be quite concrete; in the face of the evidence, why is it that the Liberian government, as an example from a much longer list of candidates, continues to rush headlong into outsourcing its education sector when the headlines all shout that this is a stupid decision.

Surely governments and corporations have a lot to lose in terms of legitimacy by such a consistent set of evidences on performance. Legitimacy, of course, was something the sociologist, Max Weber, was particularly interested in regarding the state and the conditions for political rule over a population. Governments need to be elected, and a disenchanted electorate could make its vote count in the ballot box. Right? This is something market enthusiasts also point out.

For corporations, loss of legitimacy as a fair trader and employer can hurt the bottom line, a fact that James Tooley – arch proponent of education markets serviced by large corporations – has also continued to insist on.

But if these two things are true, then why is it that governments have not been voted down, or corporations booted out from holding contracts in service sectors, as their failures mount in spectacular fashion? Instead the solution is more and more markets, rather than less.

Strategic ignorance

Linsey McGoey, a sociologist at the University of Essex, offers some interesting insights into this puzzle. She coined the concept of ‘strategic ignorance’ to describe the wilful and thus witting ignoring of evidence. She argues that despite evidence of failure, a climate of social silence emerges on unsettling facts (such as huge losses of money; poor quality services; lower wages; corruption) which then enable such activities to endure. Furthermore, such silences are then harnessed as a means of absolving the offenders from their poor practices and losses, with the promise that they will do better next time.

One example of strategic ignorance is that the rise in social inequalities could have been predicted in terms of how neoliberal theory would work in practice – as competition always has, by definition, winners and losers. Losers are more likely to be, as we have seen from the Brexit and Trump votes, those who for social and economic reasons already start with less in the competition stakes.

Similarly, the Liberian government, in deciding to outsource its education sector to venture capitalist backed Bridge International Academies, currently fighting cases in the Ugandan courts around illegal operations, could be seen as adopting a stance of strategic ignorance.

But there are costs to pay, and the costs are likely to be borne by those who are already less well-off socially. In other words, markets are not some kind of disinterested means of coordinating buying and selling. They place sellers – like large corporations-, into unequal relationship with buyers ,such as poor populations who can be ridden rough shod over, particularly when governments assume a stance of strategic ignorance.

Strategic ignorance helps us to understand the wilfully blinkered, or head in the sand stance, of governments and international agencies around education privatisation. But it seems to me that this strategy is given potency by the way in which private sector investors and factions of the political elite have joined forces. Economist Julie Froud from the University of Manchester, UK, and colleagues – in a recent article on elites and power after the 2008 financial crisis, point to the ways in which the political elites have deliberately overlooked, or looked elsewhere, regarding the failures of large conglomerates like Atos, Serco and Capita in delivering public services. This close link between private sector investors and political elites, in many cases sharing similar kinds of education biographies and social circles, tells us that Hayek was completely wrong when it comes to a disinterested market and a pervasively interested state.

Rising inequality, a political project

Both are profoundly interested in advancing and protecting their class project, which is to build up an unequal share of economic and other resources. It is this relationship that Piketty argued was part of the root cause of the rapid increase in social inequalities, especially after the financial crisis of 2008.

If education is now regarded as a sector to be invested in so as to accumulate power and resources, then corporations will–you can be sure about this–pressure the state to cave into demands for limits on the state’s financial (taxes) and regulatory (e.g. competition law/fair wages) duties toward its citizens.A complicit political class, adopting a stance of strategic ignorance toward corporate investors in education, is a dangerous combination which needs to be named and exposed.

We have a great deal to lose when we lose control over one of those social institutions – for all of its problems in making fairer worlds – to investors whose motives are not learning, but profits. Strategic ignorance by the political elites also undermines the conditions for democracy, and offers us an impoverished set of options for making better futures. Let’s take back education from the investors, and put the political elites on notice, that enough is enough.

Editor’s Note: Susan L. Robertson is Professor of Sociology of Education in the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge. Her research is concerned with the changing nature of education as a result of transformations in the wider global, regional and local economies and societies, and the changing scales on which ideas, power and politics is negotiated. Contact: slr69@cam.ac.uk

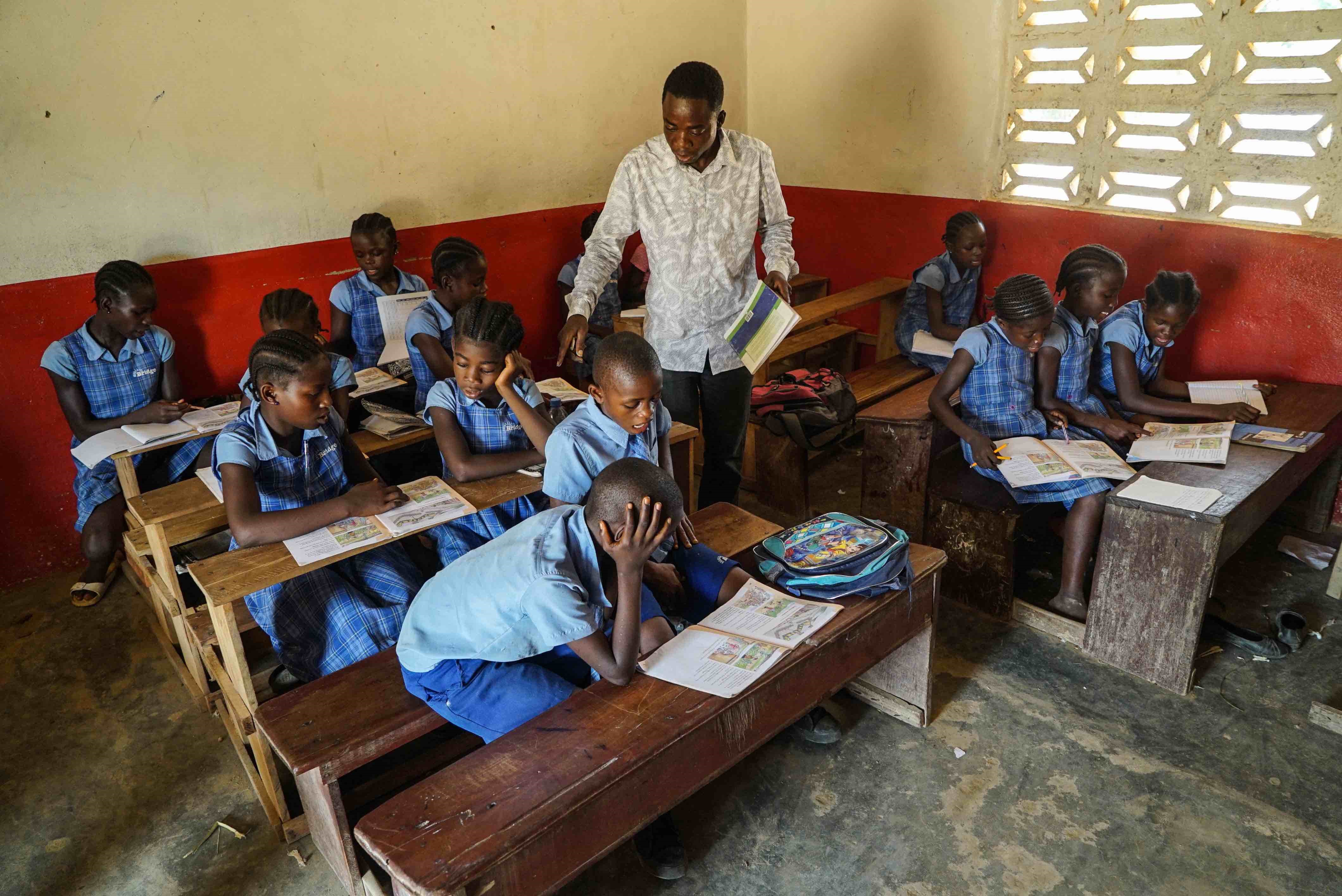

Samuel Nyah with his son Benedict, 16, a student at the Bridge-run Cinta Public School

Samuel Nyah with his son Benedict, 16, a student at the Bridge-run Cinta Public School

Latin America, leading the way in the global privatisation of education

Latin America, leading the way in the global privatisation of education

June 23rd, 2016 is etched on the nation’s memory, not only because it was a day when the pollsters, punters and polis would have their respective says and day of reckoning, but somehow life in the days that followed quite literally felt as if the earth had been jolted from its axes and shifted more than a few degrees off on a different course. Night would no longer follow day in quite the same way.

June 23rd, 2016 is etched on the nation’s memory, not only because it was a day when the pollsters, punters and polis would have their respective says and day of reckoning, but somehow life in the days that followed quite literally felt as if the earth had been jolted from its axes and shifted more than a few degrees off on a different course. Night would no longer follow day in quite the same way.